Who Suspended Rohingya Rations?

Questions for UNHCR and WFP

UNHCR’s Inspector General has, for the first time, put on record what Rohingya families have suspected all along: the biometric regime driving ration suspensions in Kutupalong and Nayapara Registered camps is mandated by the Government of Bangladesh. It means decisions that left “registered refugee” families hungry are not a mysterious UN “policy glitch” but a state-led requirement that UN humanitarians chose to implement.

This is progress of sorts. Clarity unlocks leverage. If the policy author is Dhaka, then donors and agencies must press Dhaka, and design alternatives, so that no one’s next meal depends on surrendering fingerprints and iris scans.

Bit of Background

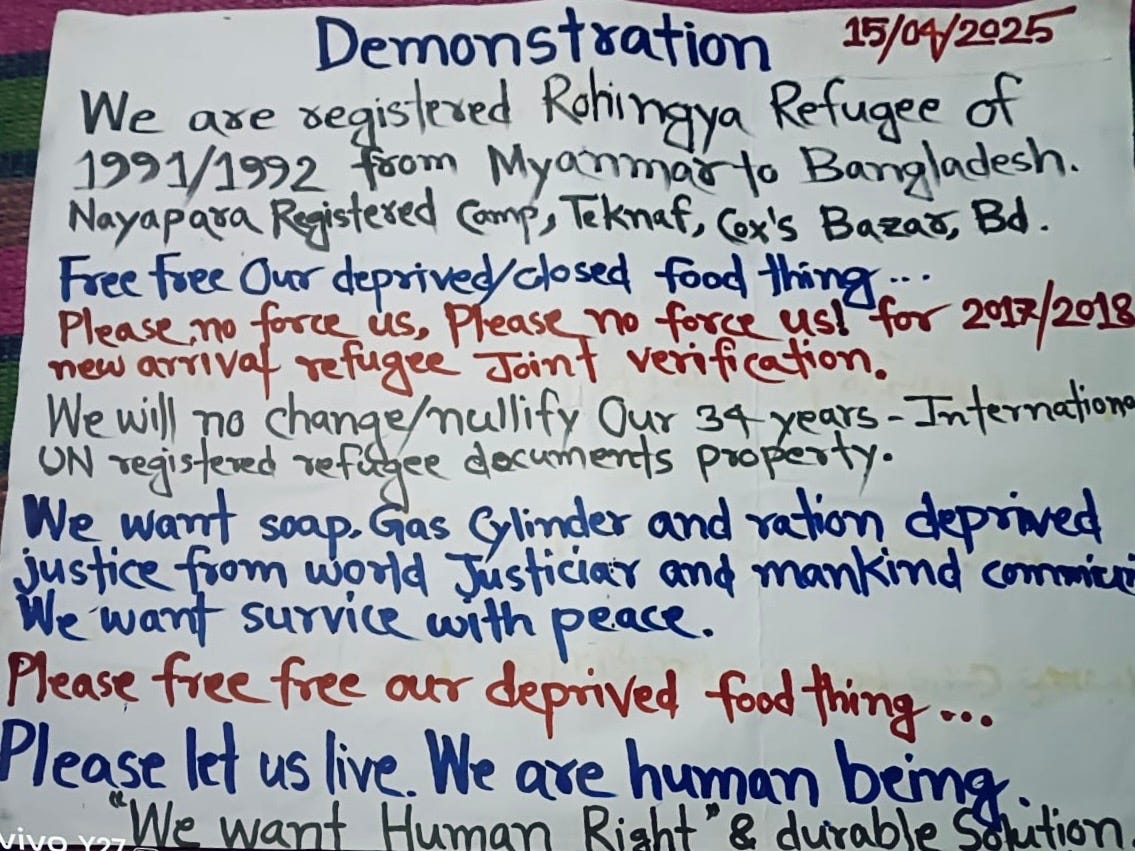

Back in March 2025, households in Nayapara and Kutupalong Registered Camps, many documented since 1991–92, were told to undergo new biometric re-verification. Refusal, they were warned, would lead to “inactivation” and loss of assistance. Around 400 families ( circa 2,000 people) stood their ground, citing fears of identity erasure (the removal of the term Rohingya from the smart card), data-sharing risks, and the bitter lesson of “neutral paperwork” later used to pressure repatriation.

In June, UNHCR responded to my questions and called biometrics “essential” and confirmed distributions were suspended pending verification. WFP too replied and said pausing rations from March was a “collective decision” tied to verified data. I reported it in The Diplomat: “Some 400 families… have been barred from receiving aid after refusing to provide biometric data.” A follow-up article showed how the justification kept circling back to “programme integrity,” not protection.

Privacy International put the core principle in one line: deploying a data-intensive system must never result in exclusion, and refusal must never lead to denial of life-saving services. (Emphasis mine.)

And yet, families are about to enter month six without food, LPG, or even soap.

What changed last week

UNHCR’s Inspector General office, replying to a letter from Mohammed Iqbal on behalf of the affected families, wrote that it is their understanding the biometric registration “is mandated by the Government of Bangladesh,” and that UNHCR is “not in a position to override government directives.” That’s the first official acknowledgement, however carefully worded, that the policy driver is Bangladesh, not a freestanding UN rule. It backs what I have reported and what refugees have thought but not vocalised for months.

The IG letter breaks the fog. By identifying where authority sits, it points directly to the actors who can fix this now. And UNHCR’s own guidance gives a blueprint: where legitimate objections exist, offer alternatives and keep assistance flowing. There’s no need to reinvent anything - just to follow the handbook and the humanitarian principles they claim to share.

Will they though?

UN humanitarians in Bangladesh have turned the ration line into a lever, withholding life-saving food from long-registered families not because they’re ineligible, but because they refused to feed a database. For five months, they’ve watched elderly women, children, and long-registered families go without rations, gas, soap or proper medical access. Indeed, recently I heard the case of a Rohingya volunteer who was told to do biometric registration by 19th August or face dismissal (video coming shortly).

Instead of designing the non-biometric workarounds, the agencies defaulted to attrition, hoping hunger would soften objections and force compliance.

WFP’s email makes the strategy plain: after “continu[ing] food assistance through February 2025,” the agency says that “in March, distributions to these households were temporarily paused….” It then notes that “the number of households completing biometric identification continues to grow…,” adding, “We are confident that all Rohingya will complete biometric registration very soon.” Read together, it sounds awfully like compliance induced by deprivation.

In WFP’s own words, the playbook is pause rations, watch “numbers… grow,” and expect “all” to comply.

What to do?

If Dhaka mandates the biometric precondition, then diplomatic pressure and donor conditionality should be directed to Dhaka - while insisting that UN agencies activate non-biometric fallbacks in the interim. UNHCR’s own rule-book is explicit: people may refuse biometrics on legitimate grounds and “alternative methods [must be] identified to ensure they can access rights and assistance.” Cutting rations pending fingerprint capture is hard to square with that. Let me give you the full text below.

From UNHCR’s own Guidance on Registration and Identity Management, Chapter 5 (“Registration as an Identity Management Process”), in the “Rights and obligations of individuals” section:

“Individuals have the right to refuse the collection of their biometrics on legitimate grounds… This does not alter their right to international protection… In such cases, individuals may be registered, and alternative methods identified to ensure they can access rights, assistance and solutions.”

Which leaves several questions - but let me just ask one to UNHCR and WFP: if your own rule-book says people may refuse biometrics and that alternatives must be identified to ensure access, why didn’t you do it in Kutupalong Registered Camp and Nayapara Registered Camp?

Why were rations, LPG, soap and routine clinic access suspended for a cohort of roughly 400 long-registered families instead of implementing a small, time-bound non-biometric channel while talks with Dhaka continued? Who authorised this departure from guidance, what harm assessment justified it, and when will assistance be restored pending a compliant workaround? If this is “programme integrity,” what on earth would coercion look like?

I am one of the Rohingya refugees who has been cut off from rations and medical services because I refused to undergo the new biometric verification in the camp. Without the biometric smart card, I am denied treatment inside the refugee camp as well as referral services at Cox’s Bazar Sadar Hospital.

I am an HIV-positive person and have been suffering for a long time without proper treatment in Bangladesh. My health condition is getting worse, but I am not receiving the essential medical care that I urgently need, only because I refused to provide biometric data.

This is a violation of basic humanitarian principles. According to UNHCR’s own policy, no one should be denied life-saving services for refusing biometrics. Yet I have been left without food, medicine, and medical access for months.

I appeal to UNHCR, WFP, the Government of Bangladesh, and the international community to immediately restore assistance and ensure that refugees like me can access life-saving treatment without being forced into biometric registration.