The Anti-Rohingya Turn in Malaysia’s Online Spaces

Content warning: This post contains racist and anti-refugee language (quoted for documentation), and references to incitement and violence.

Two days is a long time for an incitement post to sit online.

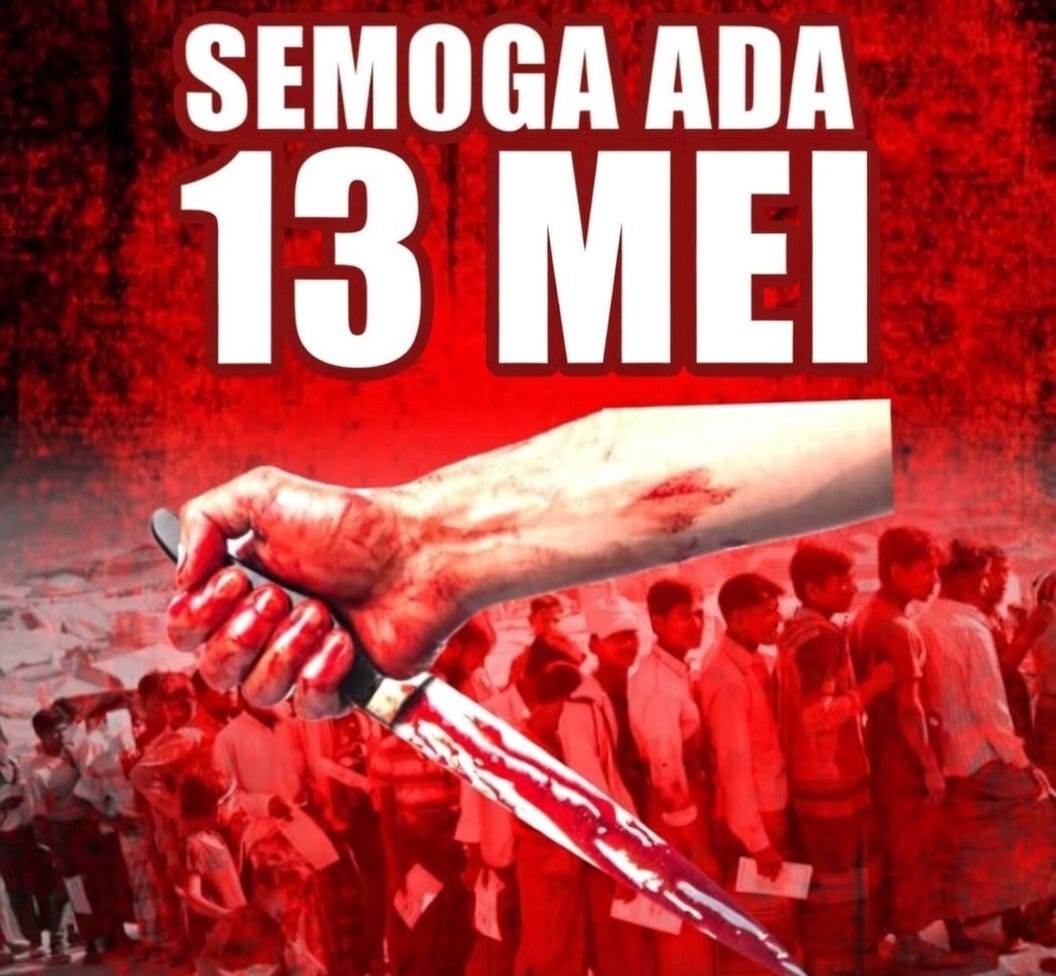

Last week, a graphic began circulating in a Malaysian Facebook space that targets PATI - Pendatang Asing Tanpa Izin (“foreigners without permits”). The image was bluntly incendiary - a bloodied knife held in a fist, overlaid with the words “SEMOGA ADA 13 MEI” - “Hopefully there will be a 13 May.”

“13 May” is not a neutral date in Malaysia. It is shorthand for the 1969 racial riots, a symbol of mass violence. And the caption attached to the image did not soften the meaning. It praised past violence, implied it should happen again, and described an unnamed target as “halal diperangi” — religiously permissible to be fought — “enemies of religion.”

The post remained up for around 48 hours, collecting roughly 420 comments, before it was removed by Facebook.

But the removal is not the story. The story is that it was thinkable, shareable, and widely engaged with. The story is the wider ecosystem that makes a post like that feel normal: a steady, repetitive stream of dehumanisation, conspiracy, and calls for harassment, much of it aimed at Rohingya.

The removed post: What the caption said (translated):

“The Malays already did it back then on 13 May.”

“Maybe they’re asking for that date to come back again.”

“And Malays are ready to give it if it’s been asked for.”

“They are halal to be fought, real enemies of the religion.”

It’s hard to read that as anything other than permission-giving: a claim that violence is justified, even religiously valid, against a stigmatised “other.” It also shows how online hate speech often works. It doesn’t always name the target explicitly in one neat sentence. It relies on shared context, dog whistles, and the sucker punch of the image.

If you want to understand the current climate, don’t focus only on whether a platform eventually removes the most extreme post. Look at what sits around it and the wall of hate that remains.

“Search ‘Rohingya Malaysia’”

A friend of mine in Penang did a simple search - “Rohingya Malaysia” - and landed on a set of public posts and groups where the tone is not about “concern” or “policy debate,” but contempt. Rohingya are framed as illegal, dirty, criminal, culturally incompatible, and fundamentally undeserving.

What follows are a few examples from that feed. I’m posting the screenshots because this is what Rohingya live under - not only insecurity in law and livelihood, but a normalised public hostility that can tip into offline harm.

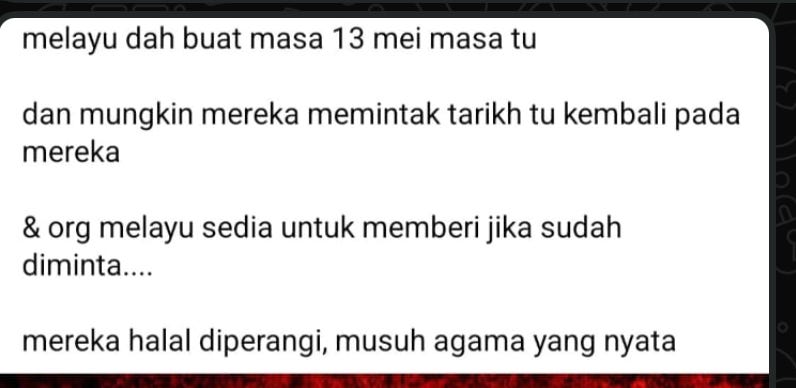

Example 1: gloating hostility, dehumanising language

One post, written in colloquial Malay, recalls that the author used to insult Rohingya online, got criticised for it, and now feels vindicated - “the same mouths who abused me before… deserve it.” This is not a policy position. It is social permission - the emotional reward of contempt, the pleasure of being “right” about a stigmatised group.

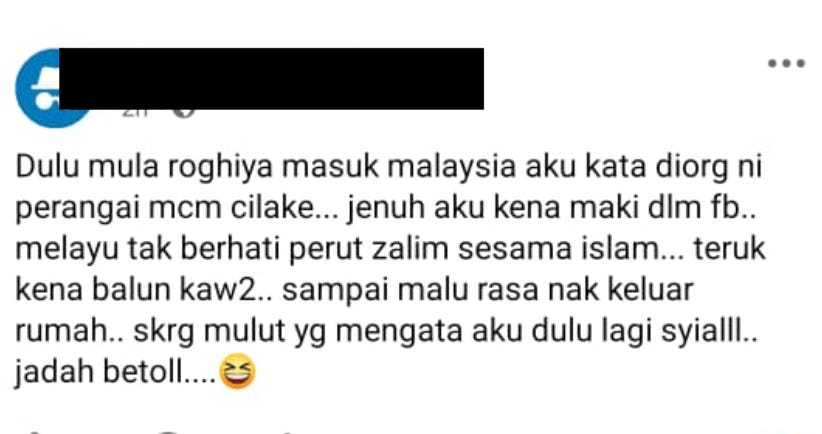

Example 2: “Rise up” rhetoric and the Aceh reference

Another post reads (translated):

“Expect the government to chase out PATI? No way. The money has already been stuffed into their pockets.”

“They don’t care about our children’s future.”

“Rise up, my people, for our beloved country.”

“Look at Aceh - how they united to drive foreigners out.”

A banner in the same post says: “Strongly reject the arrival of Rohingya refugees.”

Here Rohingya are treated not as refugees, people fleeing atrocity, but as some kind of contaminant the nation must “rise up” against. The language of corruption (“money in pockets”) also helps. It turns hate into a story of moral cleansing.

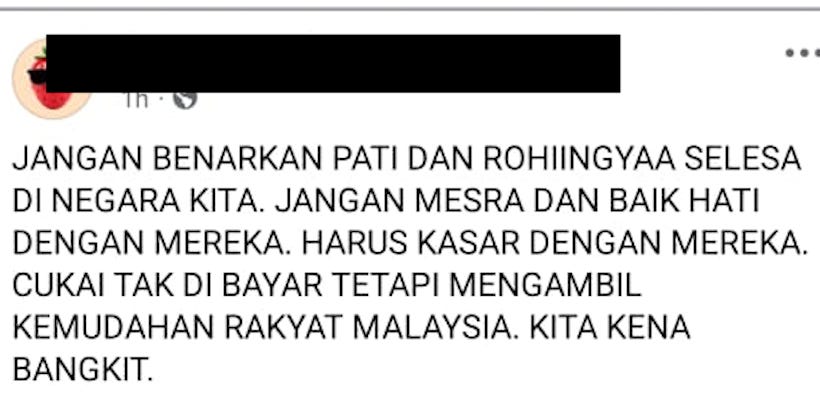

Example 3: “Don’t be kind — be harsh”

Another page posts:

“Do not allow PATI and Rohingya to live comfortably in our country.”

“Don’t be friendly or kind-hearted.”

“We must be harsh towards them.”

“They don’t pay tax but take Malaysians’ facilities.”

“We must rise.”

This is explicit advocacy of mistreatment. Not deportation through law, not a policy demand but a social instruction. Be harsh.

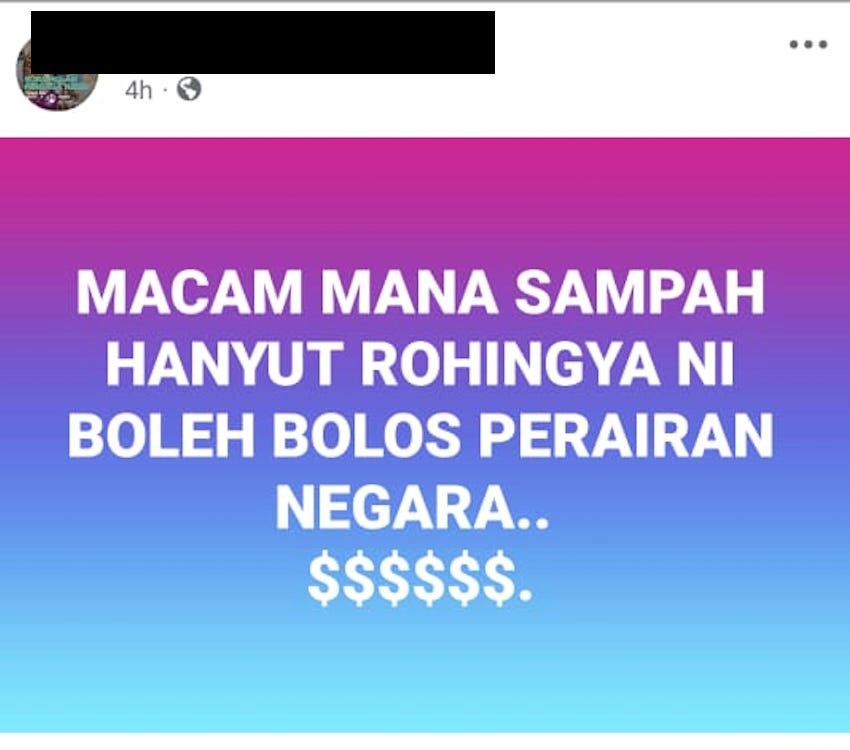

Example 4: “Drifting rubbish” and bribery insinuations

A graphic asks (translated):

“How can this ‘drifting rubbish’ Rohingya slip through our waters? $$$$$$”

The phrase used - sampah hanyut - is dehumanising. It renders human beings as trash. The “$” implies bribery. Someone must have been paid to let them through. Hate is made “reasonable” by dressing it up as anti-corruption suspicion.

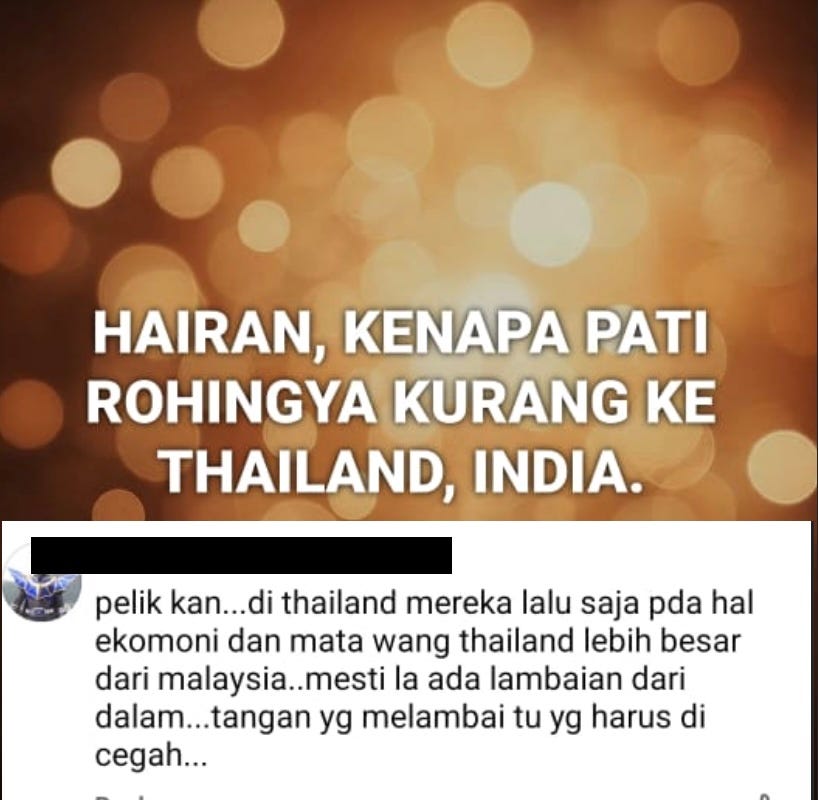

Example 5: “Why don’t they go to Thailand or India?”

Another post reads:

“Strange. Why do undocumented Rohingya go less to Thailand, India?”

A comment underneath adds:

“There must be a beckoning from inside… the hand that beckons must be stopped.”

This is how conspiracy thinking embeds itself. Rohingya are not only unwanted; they are imagined as being invited by traitorous insiders - NGOs, officials, political enemies - who must be “stopped.” The target expands.

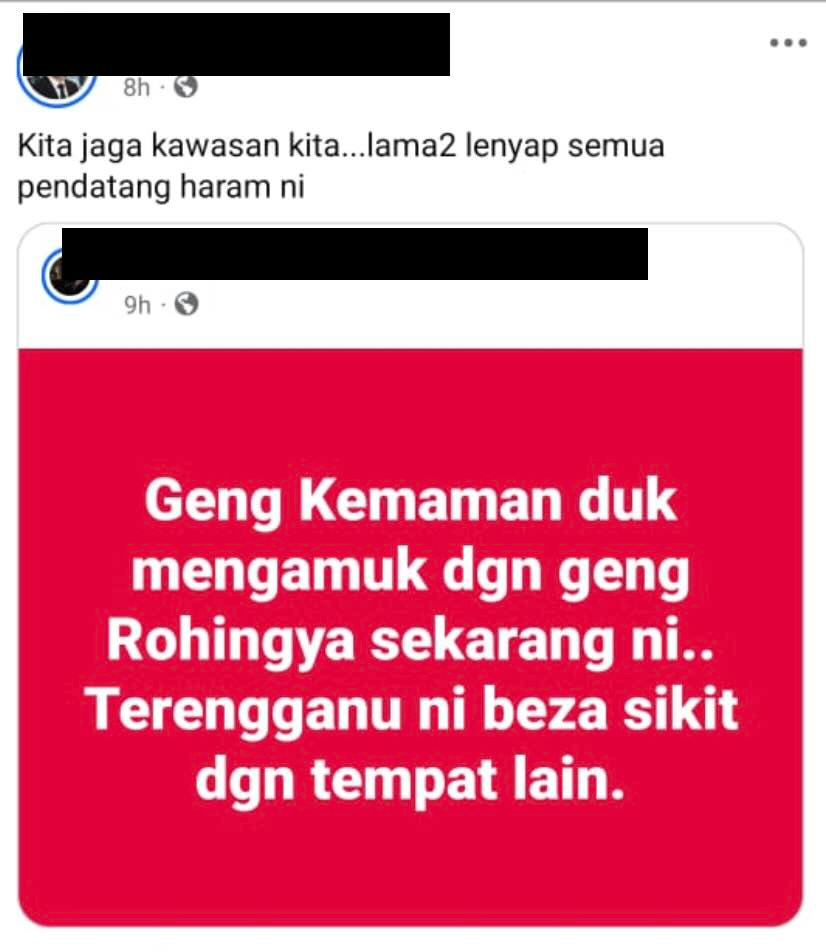

Example 6: “Sooner or later they will disappear”

One post says (translated):

“We guard our area… sooner or later all these illegal immigrants will disappear.”

It then shares another graphic claiming a local “gang” is “going on a rampage” in conflict with “the Rohingya gang.”

Even when framed as local gossip, the language is threatening: “disappear,” “rampage,” “gang” - a vocabulary that normalises vigilante imagination.

Example 7: Not only Rohingya

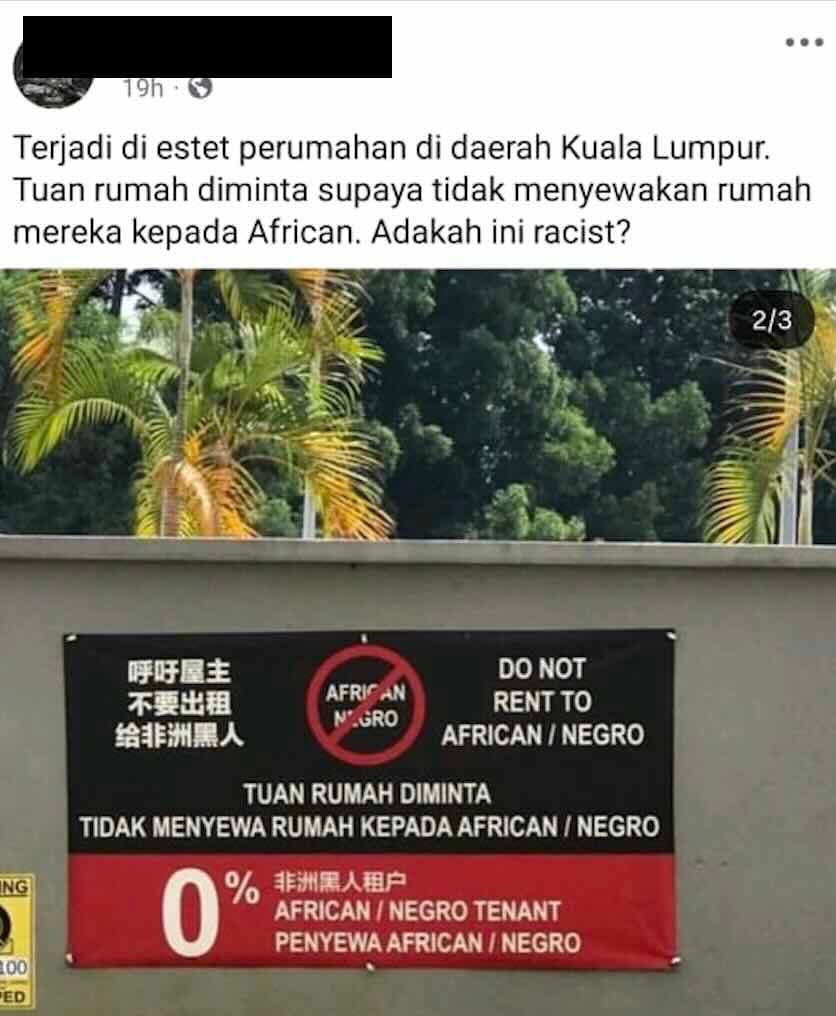

One of the posts I saw wasn’t about Rohingya at all. It showed a banner in a Kuala Lumpur housing estate reading: “DO NOT RENT TO AFRICAN / NEGRO” and “0% African tenant,” in multiple languages.

It matters because it shows the ecology. The same spaces that build hatred against Rohingya are often building hatred against migrants and racialised outsiders more broadly. Rohingya are simply one of the most vulnerable targets because Malaysia’s legal structure already casts them as “illegal.”

How did Malaysia get here?

This shift did not happen in a vacuum. Multiple studies and reporting over the past few years describe a turn from earlier sympathy (which peaked around 2015 during the Andaman Sea boat crisis) to persistent hostility, much of it amplified online.

What these posts show is not just “people being nasty online.” The antagonism has a structure and it has intensified over the last decade, sharply during and after Covid. It draws on four overlapping forces.

First, the socioeconomic story: Rohingya are framed as competitors in low-wage work, blamed for strain on local services, and caricatured as “insular” communities. Individual incidents are amplified into collective stigma - “crime”, “disease”, “dirtiness” - until a whole population is treated as a public nuisance.

Second, the legal/institutional story: because Malaysia does not recognise refugees in domestic law, Rohingya are repeatedly labelled as PATI — “illegals.” When that’s the starting point, people can excuse mistreatment as law enforcement. Rohingya are useful to the economy as cheap labour in the shadows, but unwanted as neighbours with rights.

That contradiction sits under a lot of the hostility.

Third, the political story: the public mood is not separate from politics. Leaders and influencers oscillate between symbolic humanitarianism and hard-line nationalism, often failing to challenge viral disinformation when it becomes electorally useful. Online hate does not float in mid-air; it is shaped by what the state legitimises, what parties tolerate, and what platforms monetise.

Fourth, the DPP issue: Malaysia is rolling out a government-issued Refugee Registration Document, the Dokumen Pendaftaran Pelarian (DPP). as a new ID system intended to replace reliance on UNHCR cards. Officials have said it will store refugees’ personal details and biometrics in a central government database, and that the DPP will be the only document recognised by Malaysian authorities for refugee identification.

For many Rohingya, this is not calming. It is frightening. They fear the DPP could become another tool to tighten control. To sort people into “acceptable” and “deportable,” to normalise long detention, and to make future removals easier - especially in a country where refugees still have no legal status. That anxiety is not abstract. UNHCR has said the first phase of the DPP programme will focus on registering people already held in immigration detention centres.

So the mistrust deepens. Raids continue, detention remains indefinite for many. “Registration” can feel less like protection and more like the state building a clearer list of who to arrest, hold, and remove.

Facebook removed the knife post after roughly 48 hours.. But the broader ecosystem remains - public groups, shareable graphics, dehumanising slang, insinuations of conspiracy, and repeated calls to “be harsh,” to “rise,” to make people “disappear.”

The post was taken down. The permission structure remains.

I also share shorter updates, documents, and observations, including occasional Bangla translations, on my WhatsApp channel, for material that does not always fit into longer Substack pieces. Readers are welcome to join.

The racism in Malaysia is horrible. This is a powerful piece. I hope there can be reforms. Rohingya people have suffered so terribly.