Myanmar Junta Document Exposes Shocking Healthcare Failures for Rohingya

Confidence-Building Measure Falters as Pilot Repatriation Reveals Inadequate Healthcare System for Returning Rohingya

The 20 volunteer Rohingya refugees, who visited Myanmar as part of the confidence-building measure for pilot repatriation, were handed a flimsy document outlining various plans for their return, including medical provisions. Within these pages, a limited explanation of the healthcare plans and resources was provided for the returning Rohingya community.

As I examine this document from the Myanmar junta, aimed at reassuring Rohingya refugees about the medical provisions awaiting them upon their return, I cannot help but be reminded of a poignant and devastating story from Francis Wade's book "Myanmar's Enemy Within: Buddhist Violence and the Making of a Muslim 'Other'". Wade's account provides a stark indication of the dire situation faced by the Rohingya in Myanmar.

The story revolves around a Rohingya woman whose baby was positioned upside down in her womb. Her husband, Arif, had to call the village administrator to seek permission to go to the hospital, which took an entire night for authorities to order an ambulance and a police car. Before 2012, the couple could access a hospital just minutes away, but due to new restrictions, they had to endure a gruelling three-hour journey to the nearest hospital that would treat Rohingya.

Upon arrival, the woman could barely walk. The Burmese doctor, after examining her, chastised the couple for their late arrival. Arif explained the need for permission to visit the hospital, but to no avail. Coldly, the doctor informed Arif that his wife and baby were both going to die, instructing him to take the ambulance and police car back to their village - leaving his pregnant wife alone.

Helplessly, Arif complied. He was later informed of their deaths, but he could not even obtain permission to visit their graves. This harrowing account serves as a stark reminder of the systemic and deliberate nature of healthcare deprivation that the Rohingya have faced for years.

The junta's document, rather than instilling confidence, only serves to reinforce the grim reality that the Rohingya may continue to face a healthcare system that is unable—or unwilling—to address their medical needs upon their return to Myanmar, potentially exacerbating the ongoing humanitarian crisis.

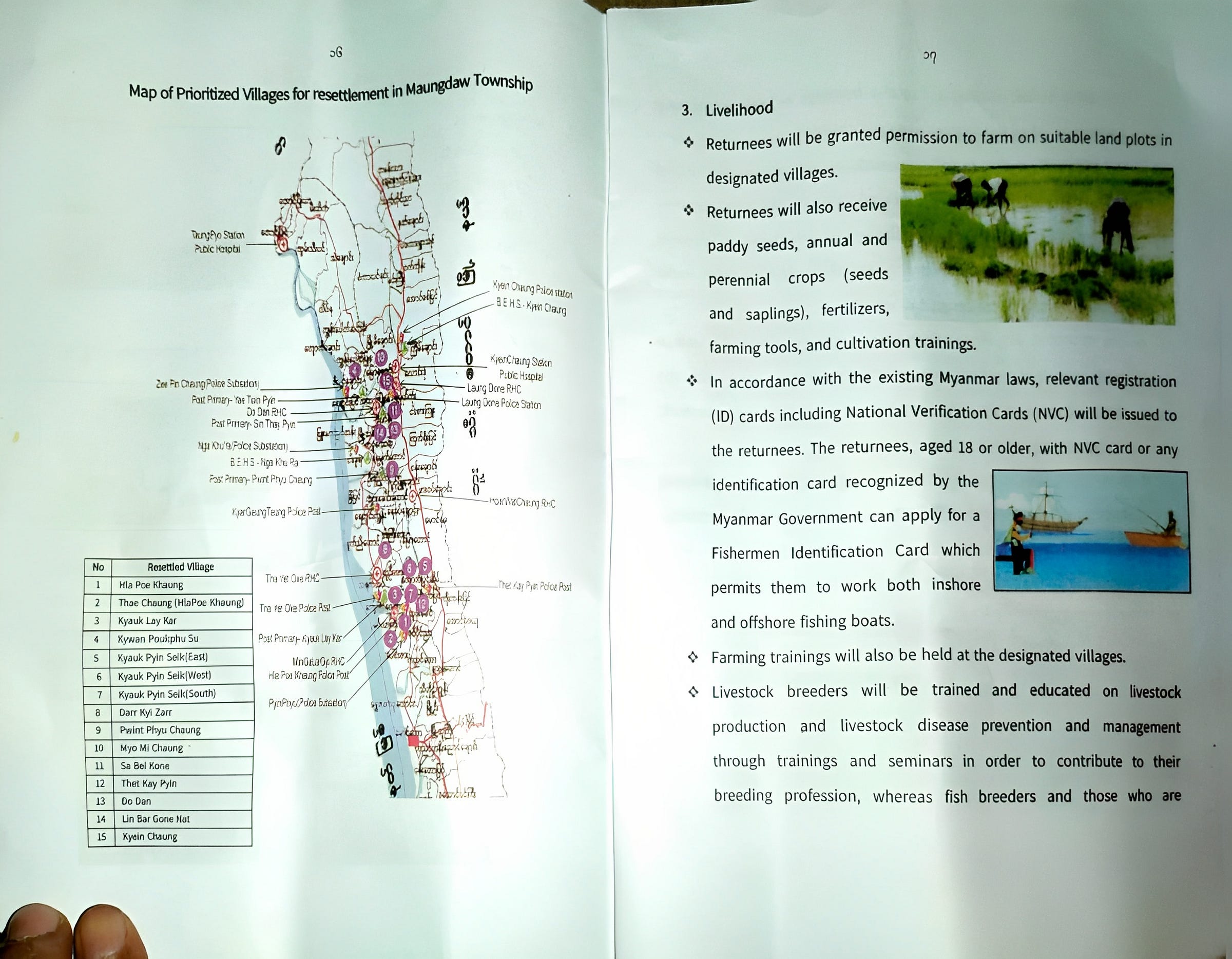

Within this document, two pages specifically addressed the healthcare plans and resources for the returning Rohingya community.

From a patient's perspective, there are several concerns and potential areas of improvement in the healthcare system described:

Inadequate resources: With a significant number of returnees, the demand for healthcare services may increase, potentially leading to overcrowded hospitals and clinics. This could result in long wait times for patients and a potential decrease in the quality of care provided.

Distance to healthcare facilities: The maximum distance between a village and a hospital is stated to be approximately 8 miles, and the minimum distance is approximately 8 furlongs. For patients with limited mobility or transportation options, this distance might pose a serious challenge in accessing healthcare services in a timely manner.

Quality of mobile clinics: While mobile clinics are intended to provide healthcare to areas far from health clinics, the quality of care provided by these mobile units might be very limited compared to what is available at hospitals and fixed clinics. This could result in wholly inadequate treatment for patients in remote areas.

Staff training and expertise: The document mentions that local medical personnel are being trained to provide comprehensive healthcare, but it does not elaborate on the level of training or expertise of these professionals. This raises concerns about the overall quality of care patients can expect, particularly for complex health issues.

Access to specialised care: It is unclear if the healthcare system described provides access to specialised care, such as mental health services, cancer treatment, or advanced surgical procedures. Patients with specific healthcare needs might face challenges in receiving appropriate treatment within this system.

Language and cultural barriers: Although the government claims to provide healthcare services to anyone without discrimination, language and cultural barriers could still hinder effective communication between healthcare providers and patients, affecting the quality of care provided.

Transparency and trust: With a history of conflict and mistrust between the government and the Rohingya population, patients might be hesitant to fully trust the healthcare system and providers. Building trust and ensuring transparency in the healthcare process is essential for patients to feel comfortable seeking care and following medical advice.

It is crucial to emphasise that the healthcare denial experienced by the Rohingya in Myanmar was not merely a case of "insufficient services." This distinction is vital, as the language of sufficiency risks diluting the severity of the genocide. In fact, the healthcare denial represents an intentional act of policy and is a critical part of the genocidal process. This was part of Raphael Lemkin's original thinking, which later translated into an article in the Genocide Convention, emphasising the creation of conditions to deny life's essentials. Severely limited nutritional intake and restricted access to healthcare are just a few elements of this genocidal process. Recognising these atrocities for what they are is a vital step in addressing the ongoing humanitarian crisis and holding those responsible accountable.

In conclusion, the handout provided to the volunteer Rohingya refugees falls drastically short of being a genuine attempt to rectify years of injustice and suffering. Instead, it comes across as a superficial document, emblematic of the junta's shallow approach to the complex issue of repatriation. This PR stunt fails to inspire confidence or address the deep-rooted problems faced by the Rohingya community. Moreover, the document reiterates the junta's insistence on the Rohingya taking up the NVC card, which only adds to the ongoing controversy surrounding their identity and citizenship. This issue will be explored further in a separate post. It is high time for the Myanmar junta to move beyond superficial measures and engage in a meaningful dialogue to address the plight of the Rohingya and ensure their safe and dignified return with full rights.