RRRC Mizanur Rahman and the Rohingya Education Crisis

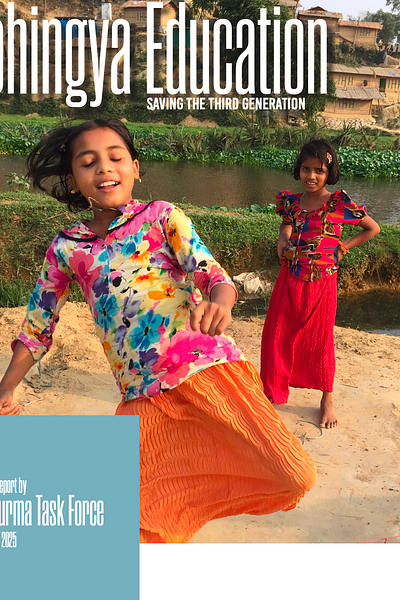

Justice For All (JFA) and Burma Task Force (BTF) recently convened an online discussion on Rohingya education, billed as bringing together Rohingya activists and a lawyer involved in the ICJ case against Myanmar. The lawyer did not ultimately participate, but the panel otherwise reflected an effort to foreground Rohingya perspectives on education in the camps.

One participant, however, stood apart.

Mizanur Rahman, Bangladesh’s Refugee Relief and Repatriation Commissioner (RRRC), joined the panel. His presence was not merely unusual. It was deeply uncomfortable.

Mizanur Rahman is not a neutral expert or an external observer. He is the senior bureaucrat who oversees the administrative system that governs the Rohingya camps. His office supervises the Camp-in-Charge (CiC) structure, which controls movement, permissions, facilities, approvals and closures across Cox’s Bazar and Bhasan Char. Education, like everything else in the camps, operates only with bureaucratic consent.

When an official with that level of authority sits alongside Rohingya speakers on a panel about education, the space is no longer neutral. The imbalance is structural. As the official who oversees camp administration, he symbolises the system under discussion, even though the format of the panel left little room to confront that system directly.

This concern is not theoretical. Mizanur Rahman has a public record that cannot be separated from any discussion about Rohingya education. In an interview with The Business Standard, he questioned whether Bangladesh “needs more” Rohingya, describing them dismissively as agricultural labourers and fishermen and asking whether a single Rohingya doctor or engineer even exists. Such remarks echo a utilitarian view of refugees that reduces them to economic value and erases the deliberate policies that have denied Rohingya children access to schooling for years.

Rahman’s comments are all the more striking given his own background. He is a beneficiary of elite education, with qualifications and training from institutions in Bangladesh and overseas. Yet he runs a system that has deliberately dismantled educational pathways for Rohingya children, and then cites the absence of doctors or engineers as evidence that integration is impossible. To ask whether Bangladesh “needs more” Rohingya on that basis is to weaponise deprivation and call it common sense.

That record matters because the RRRC’s office has presided over some of the most restrictive education policies imposed on any refugee population globally. Human Rights Watch has documented how Bangladesh shut down community-led Rohingya schools beginning in 2021, raided learning centres, confiscated materials, and threatened families who attempted to educate their children outside authorised facilities. Amnesty International and Al Jazeera have reported on the closure of madrasas and informal schools, often justified as “unauthorised,” even when no alternative education was provided.

For years, Rohingya education has been capped at basic primary levels. Secondary education was blocked entirely, leaving adolescents with no pathway forward, a situation described by the Burmese Rohingya Organisation UK (BROUK) as creating a “lost generation.” Qualified Rohingya teachers were barred from formal roles and restricted to volunteer stipends. The Myanmar curriculum, widely recognised as essential for eventual repatriation, was banned for years in NGO settings. When community groups attempted to teach it anyway, their schools were closed. Only recently, and under sustained international pressure, was a limited version of the curriculum permitted, and only for certain grades.

These restrictions intensified again in 2025 when international funding cuts forced thousands of learning centres to shut down, pushing hundreds of thousands of children out of school, as reported by Reuters and Save the Children. This educational collapse did not happen by accident. It unfolded under a policy framework overseen by the RRRC’s office.

When UNICEF and Save the Children informed the authorities on 3 June 2025 that more than 6,400 Rohingya learning centres would close “with immediate effect,” there was no public indication that the RRRC objected, imposed conditions, or demanded a phased plan to protect children. The closures affected an estimated 230,000 to 300,000 Rohingya children.

RRRC officials in Cox’s Bazar later confirmed that the office had been briefed on the decision following a meeting with UNICEF. Yet there was no public statement questioning the scale or speed of the closures, no warning about their consequences, and no visible effort to mobilise political or donor pressure to keep education services running.

This silence matters because the RRRC is not a passive observer. It is the government’s lead authority for the Rohingya response in Cox’s Bazar. The same office routinely intervenes to enforce camp layouts, restrict movement, and shut down what it deems “unauthorised” schools. When Dhaka wants a line held, the RRRC has shown it can act decisively.

In this case, that leverage was not used. There was no insistence on minimum education provision, no public demand that education be prioritised over other sectors, and no effort to challenge a decision that international agencies themselves warned would have catastrophic consequences for children.

This did not happen in a vacuum. Bangladesh has insisted on a separate, inferior education system for Rohingya children, explicitly designed to prevent integration. Learning centres were capped at primary level, formal certification was blocked, and education was treated as a temporary humanitarian service rather than a right. Donors were channelled into short-term, one-year funding cycles, making collapse predictable and permanent schooling impossible. Host-community children attend national schools; Rohingya children are confined to a parallel, fragile system that can be switched off at any moment. That is not a funding accident. It is policy.

Against this backdrop, Mizanur Rahman’s appearance on the JFA/BTF panel felt less like engagement and more like a calculated performance. He spoke the language of concern, resilience and community effort, while omitting any reference to the policies his office enforced to shut schools, criminalise informal education and cap learning at primary levels. The result was an absurd inversion - the official who presided over years of educational restriction presenting himself as a partner in solving the problem. Like an arsonist presenting himself as a fire-fighter.

JFA provided the stage; the RRRC Commissioner used it to sanitise a record that remains unaccounted for. The symbolism was difficult to miss. The discussion was streamed from Malik Mujahid’s car, with the RRRC Commissioner seated beside him, while Rohingya speakers appeared remotely. In the end, Mizanur Rahman took Justice For All - and the rest of us watching - for a ride.

JFA/BTF’s own education report helps explain why the RRRC Commissioner was invited. The report calls on Bangladeshi authorities to recognise community schools, allocate land, SIM cards and internet access, and allow international organisations greater operational freedom in the camps. All of these steps require government approval. Inviting the RRRC may therefore have been a strategic attempt to gain access, signal cooperation, or unlock permissions and funding pathways.

Such pragmatism is understandable. But it comes at a cost.

Advocacy spaces are not neutral stages. Who is invited, and how they are challenged, shapes the conversation. Placing the senior official responsible for restricting education alongside Rohingya speakers, without directly confronting his record, risks normalising that record. It shifts the discussion from accountability to optics.

JFA/BTF should appreciate that education is not a favour to be unlocked through access. It is a right that has been systematically denied. Any serious conversation about Rohingya education must begin with that fact and must confront the officials who administer the system responsible for that denial.

I share primary documents, field updates, and reporting notes on Rohingya camp issues on my WhatsApp Channel.