UNHCR’s Biometric Standoff with the Rohingya

In a UN podcast published last year, Juliette Murekeyisoni, the new interim head of UNHCR-Bangladesh, shares her experience of fleeing Burundi on the back of a lorry and discusses her commitment to displaced people. In response to a question about what she might say to those responsible for refugee suffering, she suggests she would ask something along the lines of: If those were your own children, would you leave them in a camp with no food?

The problem is that after arriving in Cox’s Bazar, she is doing just that.

On May 24th, I sent Ms Murekeyisoni some questions about 400 “registered” Rohingya families whose rations, gas and medical care were cut because they declined UNHCR’s new biometric “update.”

Silence. No acknowledgement, no explanation, no plan to feed the children she now oversees. The official who once decried “We cannot keep hope when we don’t have food” will not say why her own operation is withholding it.

Today’s post sets that public persona, refugee-turned-protector, healer of traumatised children, against the reality unfolding in Nayapara and Kutupalong, and asks, when did UNHCR’s remit become conditional on a fingerprint?

Stay tuned: in the coming days I’ll publish an in-depth report based on exclusive interviews in both Kutupalong and Nayapara, laying out what refugee camp residents really think and why their testimony raises urgent questions not just for UNHCR, but for the Government of Bangladesh itself.

But let me at least give you some of the background here.

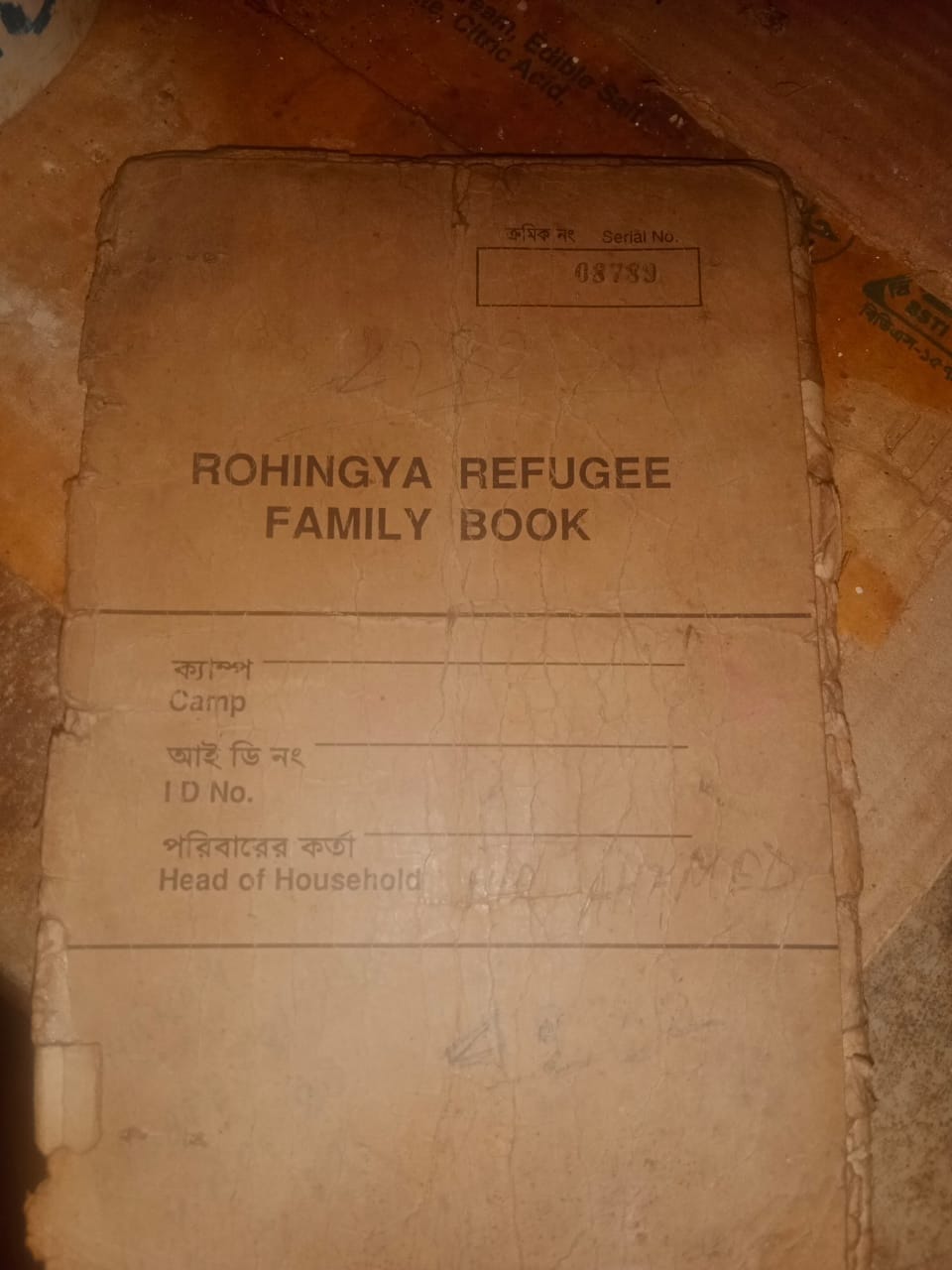

Rohingya refugees in Cox’s Bazar have been subject to successive biometric registration drives since the 2017 influx, purportedly to document identities and manage aid distribution. In 2023–2024, a renewed “registration update” targeted long-term Rohingya residents of the Nayapara and Kutupalong camps (many of whom fled Myanmar in the 1990s). This joint Government-UNHCR exercise sought to enroll biometrics (fingerprints, iris scans) for all refugees aged 5 and above, issue updated ID cards, and record family data.

Now here is the thing: participation was officially mandatory – UNHCR’s own notice warned that anyone who failed to appear would be “inactivated” in the database and “will not benefit from any assistance in future”.

They made it clear - refusal carried dire consequences. Around 400 or so families who declined biometric registration have effectively lost access to food rations, cooking fuel (LPG), soap, and even health services, leaving them in a humanitarian limbo.

Communication and Information Failures

A fundamental question is whether UNHCR adequately communicated the purposes, risks, and safeguards of biometric registration to the Rohingya. Evidence strongly indicates a failure of communication and informed consent. During the initial mass registration in 2018–2019, refugees report they were “told to register to receive aid” but not informed that their biometric data might be shared with Myanmar or used for anything beyond aid delivery. UNHCR publicly reassured refugees at the time that the data was “not linked to repatriations,” even as internally the data was intended to facilitate repatriation eligibility checks with Myanmar.

In practice, many Rohingya only discovered later that their personal details had been handed to the Myanmar government – some found their names on Myanmar’s repatriation lists and panicked. Human Rights Watch documented two cases out of a sample of 24 refugees going into hiding. Clearly then refugees were not meaningfully informed or consulted about how their data would be used, a clear breach of trust and transparency.

Human Rights Watch found that “all but one of the 24 [refugees interviewed] said that UNHCR staff told them they had to register to get the Smart Cards to access aid, and [staff] did not mention anything about sharing data with Myanmar.” One refugee even noticed after registration that the English-language receipt he was given had a box ticked “yes” to share his info with Myanmar – without his knowledge or consent (he was among the few who could read English).

These accounts flag a major communication failure. Refugees were not fully informed of the risks and procedures of the biometric exercise, nor given a real opportunity to opt out with their benefits intact.

This pattern is not unique to Cox’s Bazar. In other contexts where UNHCR rolled out biometrics, refugees likewise report scant explanation. For example, Syrian refugees in Jordan – where UNHCR began iris-scanning and biometric registration in 2012 – recalled that “They didn’t tell us what it was for, and we didn’t ask,” and virtually no one refused since “I will give my information if it means assistance”.

I am reliably informed that a 2016 internal UNHCR audit spanning five countries found inadequate information was provided to refugees in 4 out of 5 cases during biometric data collection. Such findings highlight a systemic issue - informed consent has often been treated as a formality rather than a genuine, understood choice. Refugees have taken for granted.

In Cox’s Bazar, culturally appropriate outreach and counselling were evidently insufficient. Focus groups in 2023 found that while some refugees heard basic explanations from camp leaders (majhis) or NGOs, “the organised awareness sessions did not adequately explain what they were a part of.” Many refugees, especially those who arrived traumatised in 2017, simply “did as we were told and got registered. It was a very rushed process,” as one Rohingya described. This rushed, top-down approach meant that key details (data sharing, privacy safeguards, long-term implications) were not clearly communicated. This undermined refugees’ ability to give informed consent.

Crucially, the current standoff with ~400 families (about 2000-3000 people) stems in part from UNHCR’s failure to address a specific information concern - the perceived erasure of Rohingya identity on the new biometric ID cards. According to community testimonies, the updated documents issued in 2023/24 no longer explicitly label them as “Rohingya” as earlier papers did. For a stateless people whose very identity has been systematically denied by Myanmar, this change is deeply alarming. Refugees say their “fear is not with the fingerprint or iris scan, but with what is being taken off the paper - the word ‘Rohingya.”’ They see it as a quiet negation of their history and rights.

Community elders and youth alike have voiced that “Without the word ‘Rohingya’ on our documents, it feels like our identity is being erased all over again… We are not refusing biometric registration; we are asking for recognition.” This critical concern has gone unaddressed in UNHCR’s communication. Refugees only learned of the identity omission when seeing the new cards, and no prior consent or consultation was sought about this change.

To date, humanitarian officials say community consultations are ongoing, but no official statement or adjustment has been made to reassure refugees that their ethnic identity will be appropriately reflected or why this cannot happen.

In the meantime, the affected families remain in limbo – unregistered under the new system and uncertain if their grievance is even going to be taken seriously.

According to UNHCR’s own protection guidelines, “refugees… should be informed of the purpose and expected outcome of the registration process… [and] made aware of their rights and obligations before registration takes place.” In reality, refugees got little more than half-truths and thinly veiled threats. It was a direct betrayal of UNHCR’s own mandate.

Aid Conditionality and Coercion

The insistence on biometric compliance as a condition for life-sustaining aid presents serious ethical questions. By essentially making conditional food, shelter and health care on surrendering biometric data, UNHCR has turned aid into a tool of coercion, obliterating any claim to voluntary consent. The official stance could not be clearer.

“Participation in the exercise is required… Persons who fail to show up… will not benefit from any assistance in future.”

In other words, refugees must hand over their biometric data or face starvation and destitution. As humanitarian researchers bluntly observe, “it’s harder to say ‘no’ to something when the person asking for your data also has a say over whether you eat tomorrow.”

One Rohingya man recounted that when a UNHCR officer did ask if he agreed to data-sharing, “I could not say no because I needed the Smart Card… I did not think that I could say no… and still get the card.”

Before I close, I think there is something else to consider. That is to say a “broader pattern” beyond biometrics – do humanitarian actors sometimes use refugees’ dependence to silence other forms of dissent? Historically, refugees in protracted camp situations often feel unable to protest camp conditions, corruption, or political manipulations because they fear retribution or loss of aid. In the Rohingya camps, for instance, open protest is rare. Very rare.

The situation of the 400 families is a textbook case. They voiced a legitimate concern (the erasure of “Rohingya” identity), a form of collective dissent, and the system’s response was not to accommodate that concern or defuse it but to force them into compliance by cutting off necessities.

The message is clear to the wider refugee community. No matter your grievances, you cannot afford to refuse what the aid system asks of you.

Please watch out for my full exposé. It will be published next week. I’ll share exclusive interviews from Kutupalong and Nayapara that lay bare how UNHCR and Dhaka have weaponised aid against the Rohingya.

It’s totally not acceptable. Food is human rights!

It’s totally not acceptable. Food is human rights!