What the Guardian Didn’t Say About the Rohingya Camps

How Humanitarian Reporting Erases the Architecture of Rohingya Containment

This reflection arose after reading Gordon Cole-Schmidt’s recent Guardian article on aid cuts in the Rohingya camps. It is an article that is powerful in parts but ultimately reveals how humanitarian reporting often misses the deeper political architecture behind the suffering it describes.

Ok let’s dive in.

Most newsroom coverage of aid funding cuts, like the recent withdrawal by USAID, overwhelmingly focuses on the acute suffering and loss for refugees, rather than critically examining how some aspects of the humanitarian system itself have contributed to ongoing problems. This is clear in the Rohingya context. Years of reliance on international aid have entrenched systemic issues such as restrictions on refugee rights, lack of durable solutions, cycles of dependency, and the political interests of both host and donor governments shaping aid models.

A quick review of these articles tells me one thing - editors and reporters respond to funding crises by spotlighting immediate humanitarian consequences. So you will see articles about food shortages, service cutbacks, particularly health service cutbacks, threats to education and safety etc. But you won’t see much political economy.

I suppose such coverage is vital for raising alarm and appealing for support, but it rarely interrogates how humanitarian aid is often designed around containment rather than empowerment and how humanitarian actors sometimes avoid confrontational advocacy to protect access and funding.

So why are structural critiques so rare? I wanted to ask editors about their decision-making, but as they do not reply to me even when I pitch to them (!), I doubt they would respond to any questions I have about their decision-making!

The Independent and The Guardian are both discussing the issue of aid. They both emphasise that their reporting on aid is “editorially independent,” but it is notable that their flagship coverage of global development and humanitarian crises is financed by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

This does not mean the journalism is dictated by donors, but it does help explain the persistent tilt. Articles on “Global development” tend to be narratives of crisis, shortage and rescue, not analyses that expose how aid regimes themselves can reinforce containment, dependency, and political convenience.

When coverage is structurally linked to philanthropic agendas that centre service delivery over structural critique, the result is predictable - suffering is described vividly, systems are described gently, and the deeper political architecture that produces immiseration remains politely off-stage.

Scholars such as David McCoy and Linsey McGoey have long argued that this is not accidental but embedded in the wider ecosystem of “philanthro-development” funding. The Gates model prioritises measurable, technical interventions and service delivery over political-economy analysis, structural critique or challenges to state power. It is a philosophy that treats deprivation as a problem of logistics rather than politics, and it naturally favours journalism that emphasises dramatic need, heroic service providers and quantifiable gaps in funding.

Missing, almost by design, are the stories that examine how aid regimes can entrench containment, how restrictive state policies interact with humanitarian programming, and how refugees are often governed through dependency rather than supported towards autonomy. In such an environment, the symptoms of immiseration are front-page material, but the systems that produce them rarely make it into print.

At a more day-to-day level, editors tend to prefer clear, urgent narratives. Stories framed around “disaster” move quickly; systemic critiques require time, expertise and a willingness to challenge institutional actors. Most early-career reporters head straight to the big humanitarian agencies, who dominate the information ecosystem and provide ready-made quotes and statistics. But as we have seen repeatedly in the Myanmar and Bangladesh context, these same agencies are not always incentivised to highlight their own limitations, their political compromises, or their role in sustaining the structures they operate within.

There is also the simple fact that complex political-economy critiques risk alienating donors, governments and even parts of the audience. And while this may matter less to places like The Guardian or The Independent, many outlets lack the specialist knowledge or investigative capacity to probe the “business of aid” or map the political interests that shape humanitarian practices. The result is a media landscape that reports the symptoms of crisis with urgency but rarely traces them back to the systems and incentives that produce them.

The Guardian article that prompted this reflection contains all the ingredients of that gap - a compelling account of human suffering, but delivered through a narrative frame that stops short of analysing power, intent, and political economy. It is a story that could have exposed the architecture of containment, but instead presents deprivation as an unfortunate humanitarian shortfall. In that sense, it is a missed opportunity.

Let me go through it in detail:

The Guardian article ultimately rests on the familiar humanitarian narrative of a “humanitarian collapse” brought on by an overwhelmed Bangladesh. It presents the camps as buckling under the weight of over a million refugees, services as collapsing due to a 63 percent funding deficit, and deprivation as the unintended fallout of aid cuts. In this telling, the Rohingya appear as a helpless population stranded in a tragedy that no one intended. What is missing is any sense of political economy. The framing relies on pity (emaciated children unable to feed, struggling parents, aid workers heroically fighting cuts), not power. Bangladesh is overburdened, donors have stepped back, and the resulting suffering is presented as an apolitical crisis rather than the product of deliberate policies of control.

Throughout the piece, Bangladesh is consistently depicted as a host struggling heroically against impossible circumstances. References to “the world’s largest refugee camp”, to facilities “struggling to operate”, to “services forced to close”, and to refugees who “depend on aid” all work to cast the state as a victim of global neglect. This framing deflects attention from the fact that many of the restrictions shaping Rohingya life are not accidental pressures but intentional policies of containment, restriction, and immiseration.

The article, like so many others, treats the Bangladesh’s containment policies (no work, temporary shelters, no education, no mobility etc) as simple facts of life rather than as a deliberate political strategy that has shaped its approach to the Rohingya for decades.

It centres donor cuts as the primary cause of the crisis. USAID’s withdrawal, the funding deficit, the closure of 48 health facilities - all are presented as the root explanations for deteriorating conditions. This produces a simple causal chain. Deprivation equals donor failure. But the far more uncomfortable truth that deprivation also reflects Bangladeshi state policy, humanitarian complicity, and an entrenched logic of containment is left completely untouched. By naturalising the aid system and treating Bangladesh as a passive recipient rather than an active architect of refugee camp governance, the article obscures agency where it should be examining power.

This humanitarian lens is reinforced by the portrayal of Rohingya not as political subjects but as dependent, encamped bodies. They appear as people who cannot work, cannot study, live in temporary shelters that can be dismantled at will, and queue on “factory floors” for nutrition treatment. The metaphor is meant to evoke indignity. It is like a production line of suffering, but the author never interrogates why such assembly-line management exists in the first place.

The “factory floor” is not just a shocking image; it is the logical outcome of a system built for the institutional management of a surplus population. It is a system that sustains high-volume dependency while maintaining tight control over refugee movement, labour, and possibility.

Yet the piece treats this as an unfortunate humanitarian scene rather than evidence of an intentional architecture of control. It fits perfectly into the article’s broader frame: overwhelming demand, insufficient funding, heroic service providers doing their best and helpless refugees being “processed” by necessity. It does not question whether the “factory” exists because the system is designed to keep refugees impoverished, immobile, and dependent.

In doing so, it reproduces the familiar “helpless surplus population” trope but strips it of any political economy that might explain why such dependency and immobility persist. There is no inquiry into why Bangladesh enforces immobility, what political incentives are served by disciplining a surplus population, how ministries and security agencies benefit from camp management, or how aid dependency functions as a mode of governance. The rules are described but never interpreted.

The state’s role is further softened by historical framing. Bangladesh’s push for repatriation is presented as a long-running preference dating back to the 1970s. This makes repatriation pressure seem natural, even inevitable, rather than analysing it as a political strategy to keep Rohingya in perpetual limbo while avoiding integration or rights.

Similarly, UN agencies and INGOs are depicted as heroic frontline responders crushed by donor cuts. They are protagonists in a humanitarian drama, rather than institutions that have helped uphold the very architecture of containment, accepted and administered systems of exclusion, and stabilised immobility through their programming.

Summary:

What is entirely absent from the article is the idea that containment is a deliberate political strategy rather than a regrettable failure. There is no analysis of the Rohingya as a surplus population managed through immobility. No consideration of Bangladesh’s strategic incentives to maintain the camps. No recognition of the Rohingya camp economy - extortion, micro-corruption, aid rents - that emerges around long-term encampment. And no acknowledgment of the global market for Rohingya suffering, in which humanitarian institutions, funders, and governments all benefit from the perpetuation of crisis narratives.

See my Himal article where I discuss all of this.

In the end, this is crisis reporting without politics. Vivid suffering with no examination of who benefits, who decides, and why the system is built this way. It is heartfelt, empathetic, well-intentioned, but analytically thin. It treats the Rohingya situation as an apolitical humanitarian emergency produced by donor cuts, rather than as the output of a system deliberately structured to contain, immobilise, and depoliticise a surplus population.

The crisis is engineered, not accidental. The deprivation you see is functional, not incidental; aid dependency is produced, not inevitable; and the Rohingya are governed as surplus people. On all these fronts, the Guardian piece simply fails to connect the dots.

For real-time reporting, behind-the-scenes notes, and updates that are too fast or too granular for Substack, join my new WhatsApp channel:

👉 https://whatsapp.com/channel/0029VaGYiy489inrKjYgQP37

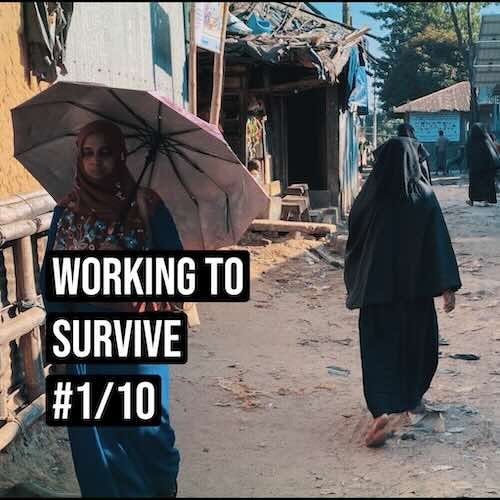

Finally, a brief note on the Working for Survival series I’ve been sharing across X and other platforms. These are testimonies from Rohingya who are forced to break the law simply to eat - an indictment of a system that criminalises basic survival. Their voices belong at the centre of any conversation about aid, rights or “solutions.” These are people whose daily work keeps their families alive despite the bans, raids and crackdowns. Their stories stand as a counter-narrative to the idea that the Rohingya are passive or dependent. Check out the series (in thread form) here

This is a really good piece. I am shocked but not surprised that after all these years, this is still how outlets like the Guardian (even the Guardian!) cover issues that are simply dripping with political economic implications. The essence is something like: oh no, the white saviours are pulling back, how will they survive without them?