Why Is Bangladesh Sealing Rohingya Camps for the 2026 Elections?

Sealing refugee camps is a classic state playbook to distract from structural democratic failure.

On February 12, 2026, Bangladesh will go to the polls for the 13th national election and a high-stakes referendum on the July Charter. Under the Interim Government led by Muhammad Yunus, this day is framed as a democratic "milestone." But in Cox’s Bazar, the air is thick with an older, darker ritual.

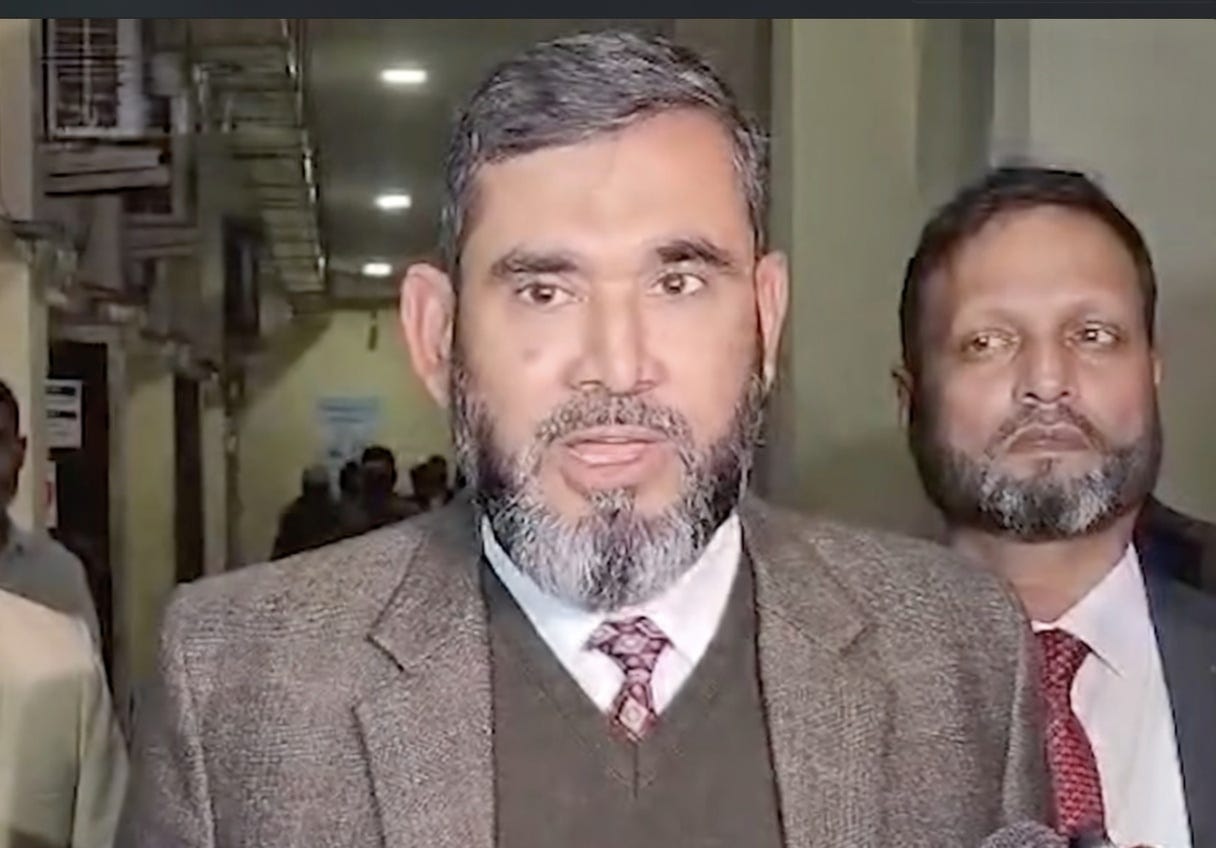

Election Commissioner Abul Fazal Mohammad Sanaullah says the camps in Ukhiya and Teknaf must be sealed before and after polling. He says Cox’s Bazar is a hub of arms trading and drug trafficking. He says this justifies joint-forces operations, arrests, and lockdown-style controls on refugee life. He said instructions have already been given to law enforcement and relevant authorities to implement this sealing of the camps.

Sanaullah made these comments as chief guest at a law‑and‑order coordination meeting on the 13th national election and referendum held at the Cox’s Bazar deputy commissioner’s office on 3–4 January 2026.

This is the Bangladesh playbook, and it is old.

When elections approach, the state looks for a safe enemy. Someone powerless. Someone who cannot vote or protest. And cannot answer back. And, once again, that enemy is the Rohingya.

Notice what is happening here.

Bangladesh has held many elections. At least seven have been deeply contested, violent, or boycotted. Ballot boxes stuffed. Voters intimidated. Opposition rallies blocked. Candidates arrested. Entire elections run without meaningful competition - including the most recent one, held without the participation of the Bangladesh Nationalist Party.

None of this had anything to do with the Rohingya.

The Rohingya did not engineer voter intimidation. They did not stuff ballot boxes. They did not force opposition parties off the field. They do not control election administration, the police, or the army. They did not install road blockades and repeatedly hurl petrol bombs at buses, trucks and rickshaws like in 2013-2015. They did not burn scores of people to death.

Yet it is their camps that must be “sealed.” This is scapegoating, dressed up as security. Bangladesh’s electoral crises did not begin with Rohingya refugees, and they will not end by sealing their camps.

Video by DBC

In the same set of remarks, the former Brigadier General characterised Cox’s Bazar as a key transit point for multiple forms of trafficking. Sanaullah said that through Cox’s Bazar “there are arms traders, there is drug business,” explicitly linking the area to illicit weapons and narcotics flows. He referred to the district’s coastal location and sea boundary as facilitating these activities. He basically said it is a hub or corridor for such trafficking. He cited these trafficking risks as part of the rationale for joint-forces operations and for sealing the Rohingya camps around the election period.

Cox’s Bazar is a coastal district with long-standing smuggling routes. That reality predates the Rohingya influx by decades. Drugs, arms, and trafficking networks did not appear because refugees arrived in 2017. They exist because of corruption, political protection, and entrenched criminal economies - all of which sit outside the camps, not inside bamboo shelters where movement is already restricted.

But blaming refugees is easier than confronting power.

International democracy assessments have been clear for years. Bangladesh is not suffering from refugee-driven electoral disorder. It is suffering from structural democratic failure. The Economist Intelligence Unit has classified Bangladesh as a hybrid regime since 2008. Freedom House rates it Partly Free, citing partisan election management, harassment of opposition, and restrictions on media and civil society.

In other words, the problem is systemic.

Sealing refugee camps does not fix ballot manipulation. Deploying joint forces does not create political competition. Nor is it a substitute for legitimacy.

What it does do is reinforce a familiar narrative: Rohingya as criminals and as a threat that must be locked down so the state can present an image of control.

This narrative serves two purposes. It reassures the domestic audience that force is being exercised somewhere. And it diverts attention away from the real causes of electoral failure - election bodies that lack independence, security forces that police politics, courts that do not provide remedy, and a system designed to manage outcomes rather than protect the vote. It is an entire edifice in which force replaces consent.

The Rohingya are stateless, disenfranchised, confined, and dependent. They are not an electoral constituency. They are not a political actor. Treating them as a security problem during elections says far more about Bangladesh’s democracy than it does about the camps.

Every time elections falter, the state reaches for the same script. And every time, the Rohingya pay the price - sealed in and blamed.

“International democracy assessments have been clear for years. Bangladesh is not suffering from refugee-driven electoral disorder. It is suffering from structural democratic failure